Trinity

Intro

This is one in a series of blog posts/articles I’m writing to describe my game design methodology. In the first article, I named the system “Trinity” – but I mentioned that I had to lay a bunch of pipe before I could describe why. I have now laid enough pipe, and in this article I’m going to go over (in the most general terms) why I called it that.

There are a lot of “things” that make up a game, and I like to break them down into three categories – like smashing an atom into a proton, a neutron, and an electron. In my method, these three categories are super-important. They apply at every level of my decision making process, so this article is going to be all about the three categories.

Previous Article | Next Article

The “Trinity”

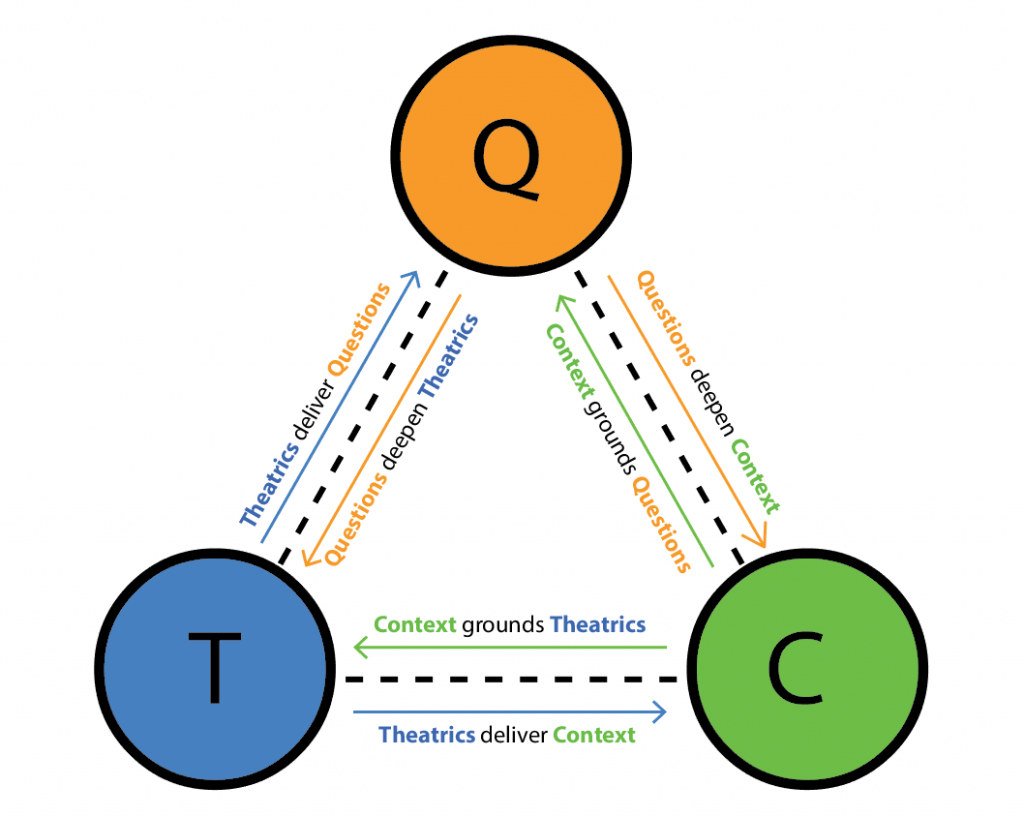

There are at least 3 basic categories that everything in a game can be broken down into, which I call “Context,” “Theatrics,” and “Questions.” All three components are equally important. They also depend on each other. Like load-bearing pillars, if one falls the others aren’t going to hold the roof up by themselves. This is so important, I’m going to restate it:

Context, Theatrics, and Questions are the building blocks of a game. All three are equally important, and they are all interdependent.

“Context” is about the creative agenda (and if you’re selling the game, the business agenda).

“Theatrics” is about flashy showiness – audio-visual aids that help the game communicate with players.

“Questions” is about interactivity – anything interactive falls into this group.

Each adds a different “flavor” to the game soup, as I’ll get into below.

Context (Spicy)

Context is the game’s “spiciness” – it’s what gives it a certain flavor, or character. Often Context is based on real-world concerns like budget or audience, but also deals with creative or artistic concerns like art style and theme.

Context is a patchwork creative agenda comprised of the needs, vision, and craft of everyone who works on a game. It is the harmony of intentions across the entire team – both at the developer and (if applicable) the publisher or money-people.

Some examples of Context in a game:

- The game’s overall art style (grounding Theatrics)

- The game’s plot

- The business model

- Supported platforms

- The game’s theme/message

- The game’s genre or intended audience (grounding Questions)

- The budget

- Etc…

Context provides the spice to a game like Chess. The game could be much more abstract (e.g. the pieces could be colored cubes with names like “piece A,” “piece B,” etc) but instead the game was themed as a medieval war with ranks of pawns, knights, bishops, fortifications, kings, and queens. The medieval war metaphor grounds the game in an idiom that makes it more understandable (and perhaps enjoyable).

Books are the most famous Context-based medium out there. Unless you’re talking about a popup or gimmick book, most books don’t use audio-visual Theatrics. The story is not usually interactive so Questions are not an issue either – the medium thrives entirely on things that fall into the group I’m calling Context.

Theatrics (Juicy)

Theatrics represent the “Juicy” parts of a game — the flashy showiness and clever trickery that often makes the difference between bad, good, or great. Theatrics are audio-visual in nature, and serve to deliver the game’s Context and Questions.

Some examples of Theatrics:

- Visual effects (particles, scrolling textures, etc)

- Musical stingers

- Cutscenes (delivering Context)

- Sound effects

- Camera shakes

- Force feedback

- Stagecraft in Player-VS-Player games

- Enemy attack telegraph animations (delivering Questions)

- Etc…

Popcap’s Peggle is a great example of theatrics all-around. But check out the video below for my favorite bit — EXTREME FEVER!!!

Theatrics provides the juice to a game like “Mouse Trap.” “Mouse Trap” is essentially “Chutes and Ladders” with great Theatrics. Check out the video below to see what I mean.

Flip the man in the pan and the ball rolls down into the rub-a-dub-tub and the cage comes down and whaaaaaaa?

Not surprisingly, Theatre and Movies are the most famous Theatrics-based medium out there. Unless you’re talking about Improvisation, Experimental Theatre, or Point Break Live, most times you go to see a play it is not interactive – same with movies – so Questions don’t come into play. You’ll notice, though, that Context is still VERY relevant (budget affects what kinds of effects you’ll be able to use, who can write your music, your plot, theme, art style, and so forth).

Questions (Crunchy)

One of the premises we’ve been building on so far in these articles is that games are fundamentally a conversation between the designer and a player. The designer asks Questions and provides the player with Tools to answer the Question.

This idea of Questions – of an interaction between the player and the designer – is central to this third, interactive axis of Trinity. Questions deepen a game.

Side note on “Crunchy”: I play a lot of tabletop RPGs – and have since I was in high school. Some of the role playing systems we used were much more complex than others, and generally the more complex they got the “crunchier” they got (referring to the amount of number-crunching you’d have to do to find out what happens). Because of this I have always associated “crunchiness” with the ways players interact with a game. The more rules there are to interact with, the crunchier it gets.

One time we played a system so complicated I couldn’t create my character without a complicated Excel spreadsheet. This was not the same game as when my friends used calculus to figure out if they could conjure enough acid to dissolve a dragon trapped inside a hemispherical wall of force, in case you were wondering.

Some examples of Questions:

- What weapon will be most effective against this enemy setup?

- What Tetris piece will drop next?

- Which building/unit should I build next?

- Should I sacrifice my knight to take the bishop?

- How do all the pieces work?

- How do I find the programmer’s hidden name in Adventure?

- Quick-time Events (QTEs) – (deepening Theatrics and Context)

(Essentially, “what are the rules” and “how can I apply them creatively.”)

Smashing Particles

I can’t go into any depth on this for this installment, but I wanted to mention this: I used the metaphor of smashing an atom earlier – but what happens when you smash it down even further? These three pillars of Trinity (Questions, Context, and Theatrics) are fractal in nature. That means if you smash any one of them open, you’ll see all three of them inside.

Split a game into these three parts, and any further split will also break down into these three parts – just smaller.

No matter what I’m using it for, I view every aspect of a game through this lens. When I design a puzzle, I consider all three. When I write a story, I consider all three. When I decide what technology to use, I consider all three.

And so on, forever. No matter how far down I go into a game’s design or production, I see whatever I’m looking at through these three pillars.

What do I use it for?

Mostly I use it when I’m designing a feature to make sure I consider every angle. As I mentioned above, this doesn’t matter how big or small, meta or micro, the feature is – I try to see how all three parts apply.

I sometimes use it to break down games when I’m studying them to see what I can use, but that’s not mainly how I apply it.

Next Time

I’m going to take a short break from writing Trinity articles. Next week is going to be on Enemy Design and the kinds of questions they ask in a combat game. When I do come back to Trinity, I’m going to try to show how I apply the things I’ve discussed so far to specific problems, linking back to these first 9 articles if I use a concept that needs more explanation than the article will allow.

Patreon Credits

As always, these articles wouldn’t be possible without my supporters on Patreon: (http://www.patreon.com/mikedodgerstout):

Champions

Petrov Neutrino

Guardians

Aidan Price

Martin Ka’ai Cluney

Patrons

François Rizzo

Ryan Auld

Genevieve Pratt

Jesse Pattinson

Nikhil Suresh

Teal Bald

Vincent Baker

Benefactors

Justin Keverne

Ben Strickland

Mad Jack McMad

Oliver Linton

Katie Streifel

Annie Mitsoda

Supporters

Margaret Spiller

Jason VandenBerghe

The Yuanxian

Backers

Kim Acuff Pittman

Karl Kovaciny

Joel S.

Neal Laurenza

Christopher Parsons

David Weis

Matt Juskelis

Mary Stout

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.